How to read/write arbitrary bits in C/C++

Solution 1

Some 2+ years after I asked this question I'd like to explain it the way I'd want it explained back when I was still a complete newb and would be most beneficial to people who want to understand the process.

First of all, forget the "11111111" example value, which is not really all that suited for the visual explanation of the process. So let the initial value be 10111011 (187 decimal) which will be a little more illustrative of the process.

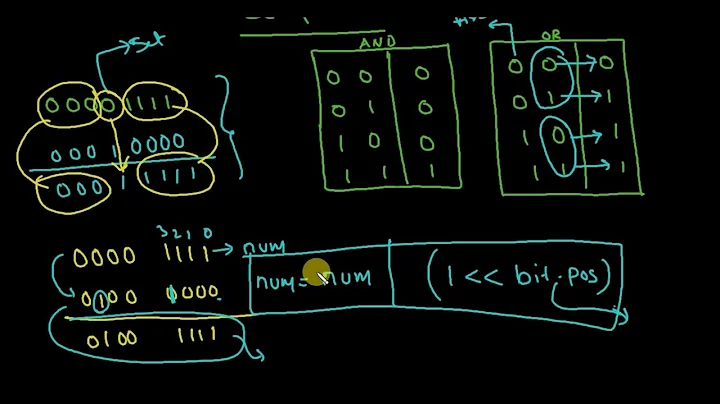

1 - how to read a 3 bit value starting from the second bit:

___ <- those 3 bits

10111011

The value is 101, or 5 in decimal, there are 2 possible ways to get it:

- mask and shift

In this approach, the needed bits are first masked with the value 00001110 (14 decimal) after which it is shifted in place:

___

10111011 AND

00001110 =

00001010 >> 1 =

___

00000101

The expression for this would be: (value & 14) >> 1

- shift and mask

This approach is similar, but the order of operations is reversed, meaning the original value is shifted and then masked with 00000111 (7) to only leave the last 3 bits:

___

10111011 >> 1

___

01011101 AND

00000111

00000101

The expression for this would be: (value >> 1) & 7

Both approaches involve the same amount of complexity, and therefore will not differ in performance.

2 - how to write a 3 bit value starting from the second bit:

In this case, the initial value is known, and when this is the case in code, you may be able to come up with a way to set the known value to another known value which uses less operations, but in reality this is rarely the case, most of the time the code will know neither the initial value, nor the one which is to be written.

This means that in order for the new value to be successfully "spliced" into byte, the target bits must be set to zero, after which the shifted value is "spliced" in place, which is the first step:

___

10111011 AND

11110001 (241) =

10110001 (masked original value)

The second step is to shift the value we want to write in the 3 bits, say we want to change that from 101 (5) to 110 (6)

___

00000110 << 1 =

___

00001100 (shifted "splice" value)

The third and final step is to splice the masked original value with the shifted "splice" value:

10110001 OR

00001100 =

___

10111101

The expression for the whole process would be: (value & 241) | (6 << 1)

Bonus - how to generate the read and write masks:

Naturally, using a binary to decimal converter is far from elegant, especially in the case of 32 and 64 bit containers - decimal values get crazy big. It is possible to easily generate the masks with expressions, which the compiler can efficiently resolve during compilation:

- read mask for "mask and shift":

((1 << fieldLength) - 1) << (fieldIndex - 1), assuming that the index at the first bit is 1 (not zero) - read mask for "shift and mask":

(1 << fieldLength) - 1(index does not play a role here since it is always shifted to the first bit - write mask : just invert the "mask and shift" mask expression with the

~operator

How does it work (with the 3bit field beginning at the second bit from the examples above)?

00000001 << 3

00001000 - 1

00000111 << 1

00001110 ~ (read mask)

11110001 (write mask)

The same examples apply to wider integers and arbitrary bit width and position of the fields, with the shift and mask values varying accordingly.

Also note that the examples assume unsigned integer, which is what you want to use in order to use integers as portable bit-field alternative (regular bit-fields are in no way guaranteed by the standard to be portable), both left and right shift insert a padding 0, which is not the case with right shifting a signed integer.

Even easier:

Using this set of macros (but only in C++ since it relies on the generation of member functions):

#define GETMASK(index, size) ((((size_t)1 << (size)) - 1) << (index))

#define READFROM(data, index, size) (((data) & GETMASK((index), (size))) >> (index))

#define WRITETO(data, index, size, value) ((data) = (((data) & (~GETMASK((index), (size)))) | (((value) << (index)) & (GETMASK((index), (size))))))

#define FIELD(data, name, index, size) \

inline decltype(data) name() const { return READFROM(data, index, size); } \

inline void set_##name(decltype(data) value) { WRITETO(data, index, size, value); }

You could go for something as simple as:

struct A {

uint bitData;

FIELD(bitData, one, 0, 1)

FIELD(bitData, two, 1, 2)

};

And have the bit fields implemented as properties you can easily access:

A a;

a.set_two(3);

cout << a.two();

Replace decltype with gcc's typeof pre-C++11.

Solution 2

You need to shift and mask the value, so for example...

If you want to read the first two bits, you just need to mask them off like so:

int value = input & 0x3;

If you want to offset it you need to shift right N bits and then mask off the bits you want:

int value = (intput >> 1) & 0x3;

To read three bits like you asked in your question.

int value = (input >> 1) & 0x7;

Solution 3

just use this and feelfree:

#define BitVal(data,y) ( (data>>y) & 1) /** Return Data.Y value **/

#define SetBit(data,y) data |= (1 << y) /** Set Data.Y to 1 **/

#define ClearBit(data,y) data &= ~(1 << y) /** Clear Data.Y to 0 **/

#define TogleBit(data,y) (data ^=BitVal(y)) /** Togle Data.Y value **/

#define Togle(data) (data =~data ) /** Togle Data value **/

for example:

uint8_t number = 0x05; //0b00000101

uint8_t bit_2 = BitVal(number,2); // bit_2 = 1

uint8_t bit_1 = BitVal(number,1); // bit_1 = 0

SetBit(number,1); // number = 0x07 => 0b00000111

ClearBit(number,2); // number =0x03 => 0b0000011

Solution 4

You have to do a shift and mask (AND) operation. Let b be any byte and p be the index (>= 0) of the bit from which you want to take n bits (>= 1).

First you have to shift right b by p times:

x = b >> p;

Second you have to mask the result with n ones:

mask = (1 << n) - 1;

y = x & mask;

You can put everything in a macro:

#define TAKE_N_BITS_FROM(b, p, n) ((b) >> (p)) & ((1 << (n)) - 1)

Solution 5

"How do I for example read a 3 bit integer value starting at the second bit?"

int number = // whatever;

uint8_t val; // uint8_t is the smallest data type capable of holding 3 bits

val = (number & (1 << 2 | 1 << 3 | 1 << 4)) >> 2;

(I assumed that "second bit" is bit #2, i. e. the third bit really.)

Related videos on Youtube

dtech

Updated on February 03, 2021Comments

-

dtech over 3 years

Assuming I have a byte b with the binary value of 11111111

How do I for example read a 3 bit integer value starting at the second bit or write a four bit integer value starting at the fifth bit?

-

Salepate almost 12 yearsYou have to work with bit operations, such as &, <<, >>, |

-

Bo Persson almost 12 yearspossible duplicate of How can I access specific group of bits from a variable in C?

Bo Persson almost 12 yearspossible duplicate of How can I access specific group of bits from a variable in C? -

Brian Vandenberg almost 9 yearsA more general answer to this question, though aimed at non-newbs (to borrow your descriptive word): get the book Hacker's Delight. Most of the recipes in that book a normal person would never have to implement, but if what you need is a cookbook for bit twiddling it's probably the best book on the subject.

-

dtech almost 9 years@BrianVandenberg - the idea of the question was to understand how bit access essentially works, not some uber leet haxor tricks which will leave people scratching their heads. Plus last year SO changed its policy toward book suggestions and such.

-

Brian Vandenberg almost 9 yearsYour response initially caused me to want to walk away, though I feel compelled to still try to help you. Where "Mastering Regular Expressions" is widely considered the best reference book on the subject, Hacker's Delight is the best reference book for /learning/ how to do bit manipulations. The algorithms are explained and proofs (or sketches of them) are given throughout the book. If the reader is left scratching their head over the algorithms, it will have more to do with their inexperience than the book.

-

dtech almost 9 years@BrianVandenberg - you still moping? If you feel like there is a better and more intuitive way to explain arbitrary bit access, feel free to post your answer as well, or copy one from your beloved book. I don't know about that particular book, but when I hear "hack" my first though is "hacky", or not immediately or clearly obvious. That might not be the case with that book, it might be just a flashy name and its content might not be "hacky" but that's hardly my fault. Take it easy now. And remember, SO is no longer about book recommendations.

-

Michael Pacheco over 4 years

Michael Pacheco over 4 years

-

-

Geoffrey almost 12 yearsIts much easier to just use

0x7as it is the same as0b111, which is the same as(1 << 2 | 1 << 3 | 1 << 4). Also your shifting to the 3rd bit, not the 2nd. -

Esailija almost 12 yearsYou also need to shift back to the right by 2 to get a number between 0-7. Also, the mask can be simplified just by using

0x1c -

Admin almost 12 years@Geoffrey see the last sentence about bit numbering. Also, any decent compiler will optimize out the verbose shift-and-or part, and at least you can see at first glance what you are/were doing.

Admin almost 12 years@Geoffrey see the last sentence about bit numbering. Also, any decent compiler will optimize out the verbose shift-and-or part, and at least you can see at first glance what you are/were doing. -

Geoffrey almost 12 yearsIf you want to make it simpler just use the 0b syntax, that shift logic, while will be compiled out is a nightmare to read, eg

(number >> 2) & 0b111 -

Admin almost 12 years@Geoffrey what's that 0b syntax? It's not standard C.

Admin almost 12 years@Geoffrey what's that 0b syntax? It's not standard C. -

Geoffrey almost 12 yearsI might have it confused with another language, or GCC accepts it, but yes your right, not standard C.

-

Jonathan Leffler almost 9 yearsThere's a bit more work to do to translate the final sample to C. You need

Jonathan Leffler almost 9 yearsThere's a bit more work to do to translate the final sample to C. You needtypedef struct A A;for the definition ofato work. Also in C, you cannot define the functions in the scope of the structure, which means some major changes are needed (you need to pass the structure to the functions, etc — the notational changes are non-negligible). -

dtech almost 9 yearsYou are correct. I wasn't focusing strictly on C, since the original question was tagged C++ as well. It could still be applied in C but with "fake" member functions, i.e. manually pass an explicit

this(or better yetselffor C++ compiler compatibility) pointer. -

dtech over 8 yearsThe reason I don't like bitfields is the standard does not specify an implementations. There is no guarantee the layout will be the same on different platforms. Doing it manually ensures that and allows for quick and efficient bulk binary serialization/deserialization.

-

tommy.carstensen over 7 yearsWhere do you define

tommy.carstensen over 7 yearsWhere do you definevalue? Is it an array of characters? Thanks! -

dtech over 7 years@tommy.carstensen - I am not sure I understand your question, the value is just an unsigned integer, for brevity represented as a single byte.

![#37 [C++]. Toán Tử Bit Trong C++ | Bitwise Operators](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/sfa7X7TnBzk/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEcCNAFEJQDSFXyq4qpAw4IARUAAIhCGAFwAcABBg==&rs=AOn4CLDlCBxhDGmuUYVrO-QERCFWAenlnA)

![[Lập trình C] Phép toán trên bit](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/KZOJk4yUIgY/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEcCNAFEJQDSFXyq4qpAw4IARUAAIhCGAFwAcABBg==&rs=AOn4CLBcPn-PH8tCn6foZt8IYTZ1t4Q1pg)