Setting variable to NULL after free

Solution 1

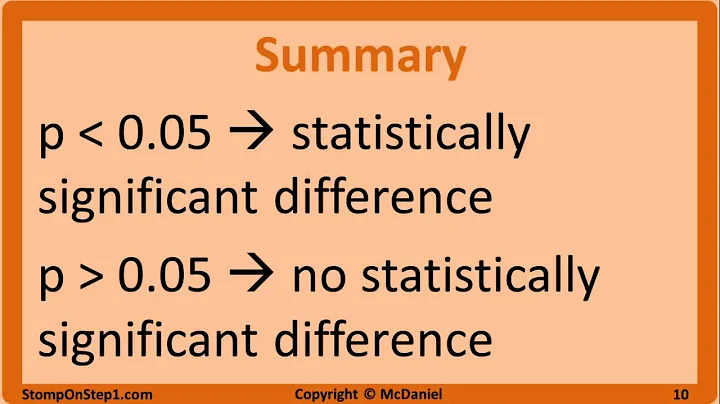

Setting unused pointers to NULL is a defensive style, protecting against dangling pointer bugs. If a dangling pointer is accessed after it is freed, you may read or overwrite random memory. If a null pointer is accessed, you get an immediate crash on most systems, telling you right away what the error is.

For local variables, it may be a little bit pointless if it is "obvious" that the pointer isn't accessed anymore after being freed, so this style is more appropriate for member data and global variables. Even for local variables, it may be a good approach if the function continues after the memory is released.

To complete the style, you should also initialize pointers to NULL before they get assigned a true pointer value.

Solution 2

Most of the responses have focused on preventing a double free, but setting the pointer to NULL has another benefit. Once you free a pointer, that memory is available to be reallocated by another call to malloc. If you still have the original pointer around you might end up with a bug where you attempt to use the pointer after free and corrupt some other variable, and then your program enters an unknown state and all kinds of bad things can happen (crash if you're lucky, data corruption if you're unlucky). If you had set the pointer to NULL after free, any attempt to read/write through that pointer later would result in a segfault, which is generally preferable to random memory corruption.

For both reasons, it can be a good idea to set the pointer to NULL after free(). It's not always necessary, though. For example, if the pointer variable goes out of scope immediately after free(), there's not much reason to set it to NULL.

Solution 3

Setting a pointer to NULL after free is a dubious practice that is often popularized as a "good programming" rule on a patently false premise. It is one of those fake truths that belong to the "sounds right" category but in reality achieve absolutely nothing useful (and sometimes leads to negative consequences).

Allegedly, setting a pointer to NULL after free is supposed to prevent the dreaded "double free" problem when the same pointer value is passed to free more than once. In reality though, in 9 cases out of 10 the real "double free" problem occurs when different pointer objects holding the same pointer value are used as arguments for free. Needless to say, setting a pointer to NULL after free achieves absolutely nothing to prevent the problem in such cases.

Of course, it is possible to run into "double free" problem when using the same pointer object as an argument to free. However, in reality situations like that normally indicate a problem with the general logical structure of the code, not a mere accidental "double free". A proper way to deal with the problem in such cases is to review and rethink the structure of the code in order to avoid the situation when the same pointer is passed to free more than once. In such cases setting the pointer to NULL and considering the problem "fixed" is nothing more than an attempt to sweep the problem under the carpet. It simply won't work in general case, because the problem with the code structure will always find another way to manifest itself.

Finally, if your code is specifically designed to rely on the pointer value being NULL or not NULL, it is perfectly fine to set the pointer value to NULL after free. But as a general "good practice" rule (as in "always set your pointer to NULL after free") it is, once again, a well-known and pretty useless fake, often followed by some for purely religious, voodoo-like reasons.

Solution 4

This is considered good practice to avoid overwriting memory. In the above function, it is unnecessary, but oftentimes when it is done it can find application errors.

Try something like this instead:

#if DEBUG_VERSION

void myfree(void **ptr)

{

free(*ptr);

*ptr = NULL;

}

#else

#define myfree(p) do { void ** p_tmp = (p); free(*(p_tmp)); *(p_tmp) = NULL; } while (0)

#endif

The DEBUG_VERSION lets you profile frees in debugging code, but both are functionally the same.

Edit: Added do ... while as suggested below, thanks.

Solution 5

If you reach pointer that has been free()d, it might break or not. That memory might be reallocated to another part of your program and then you get memory corruption,

If you set the pointer to NULL, then if you access it, the program always crashes with a segfault. No more ,,sometimes it works'', no more ,,crashes in unpredictible way''. It's way easier to debug.

Related videos on Youtube

Alphaneo

An electrical engineer, who is a programmer by profession

Updated on July 24, 2020Comments

-

Alphaneo almost 4 years

In my company there is a coding rule that says, after freeing any memory, reset the variable to

NULL. For example ...void some_func () { int *nPtr; nPtr = malloc (100); free (nPtr); nPtr = NULL; return; }I feel that, in cases like the code shown above, setting to

NULLdoes not have any meaning. Or am I missing something?If there is no meaning in such cases, I am going to take it up with the "quality team" to remove this coding rule. Please advice.

-

Mouradif almost 8 yearsit is always useful to be able to check if

Mouradif almost 8 yearsit is always useful to be able to check ifptr == NULLbefore doing anything with it. If you don't nullify your free'd pointers you'd getptr != NULLbut still unusable pointer. -

Константин Ван over 7 yearsDangling pointers can lead to exploitable vulnerabilities such as Use-After-Free.

Константин Ван over 7 yearsDangling pointers can lead to exploitable vulnerabilities such as Use-After-Free.

-

-

jamil ahmed almost 15 yearsOn Windows, at least, debug builds will set the memory to 0xdddddddd so when you use a pointer to deleted memory you know right away. There should be similar mechanisms on all platforms.

-

Erich Kitzmueller almost 15 yearsIn many cases, where a NULL pointer makes no sense, it would be preferable to write an assertion instead.

-

Mark Ransom almost 15 yearsThe macro version has a subtle bug if you use it after an if statement without brackets.

-

jmucchiello almost 15 yearsWhat's with the (void) 0? This code do: if (x) myfree(&x); else do_foo(); becomes if (x) { free(*(&x)); *(&x) = null; } void 0; else do_foo(); The else is an error.

-

jmucchiello almost 15 yearsThat macro is a perfect place for the comma operator: free((p)), *(p) = null. Of course the next problem is it evaluates *(p) twice. It should be { void* _pp = (p); free(*_pp); *_pp = null; } Isn't the preprocessor fun.

-

Steve Jessop almost 15 yearsThe program does not always crash with a segfault. If the way you access the pointer means that a large enough offset is applied to it before dereferencing, then it may reach addressable memory: ((MyHugeStruct *)0)->fieldNearTheEnd. And that's even before you deal with hardware that doesn't segfault on 0 access at all. However, the program is more likely to crash with a segfault.

-

Paul Biggar over 14 yearsI don't understand why you would "initialize pointers to NULL before they get assigned a true pointer value"?

-

Martin v. Löwis over 14 years@Paul: In the specific case, the declaration could read

int *nPtr=NULL;. Now, I would agree that this would be redundant, with a malloc following right in the next line. However, if there is code between the declaration and the first initialization, somebody might start using the variable even though it has no value yet. If you null-initialize, you get the segfault; without, you might again read or write random memory. Likewise, if the variable later gets initialized only conditionally, later faulty accesses should give you instant crashes if you remembered to null-initialize. -

Paul Biggar over 14 years@Martin v. Löwis: Ah, you're assuming old-school C where the declarations are at the top of the function? Fair enough then.

-

Amber over 14 yearsYou can actually just call free() without checking - free(NULL) is defined as doing nothing.

-

Stefan over 14 yearsDoesn't that hide bugs? (Like freeing too much.)

-

StevenWang over 14 yearsif i pre-check whether the pointer has been freed already, like

StevenWang over 14 yearsif i pre-check whether the pointer has been freed already, likeif(p!=null){.....}, is it unnecessary to set it NULL? -

Stefan over 14 years@Macroideal: No, you set it to

NULLso that you can pre-check it. (or just callfree()again.) -

sharptooth over 14 years@Macroideal. Yes, it is. free() doesn't change the pointer value. So the check will evaluate to "true" and free() will be called again for an address of already freed block.

-

RageZ over 14 years@Macroideal: no it doesn't change a thing, you have better to set it to NULL anyway just to be safe.

-

DrPizza over 14 years@gs: Yup, it's a horrid practice. Double free is a logical error; you don't want logical errors to be hidden, you want them to blow up noisily and immediately.

-

StevenWang over 14 yearsthanx, I got it. i tried :

StevenWang over 14 yearsthanx, I got it. i tried :p = (char *)malloc(.....); free(p); if(p!=null) //p!=null is true, p is not null although freed { free(p); //Note: checking doesnot prevent error here } -

visual_learner over 14 yearsClarifying on @sharptooth:

free()can't change the pointer value. To do so it would have to befree(void **ptr)or be a macro#define free(x) do { __real_free(x); x = NULL; } while(0)to do that. -

visual_learner over 14 years@DrPizza - An error (in my opinion) is something that causes your program not to work as it's supposed to. If a hidden double free breaks your program, it's an error. If it works exactly how it was intended to, it's not an error.

-

StevenWang over 14 years@Chris Lutz so, what the is inner details of the

StevenWang over 14 years@Chris Lutz so, what the is inner details of thefree(), what changes happened after we called thefree(), kinda puzzled -

visual_learner over 14 yearsThe C runtime has a memory management system in

malloc()andfree()(and friends). Basically, when you callmalloc()the system marks of a chunk of memory as "used" and then gives it to you, and when you callfree()it marks that chunk of memory as "unused" and does whatever it wants with it (like give it to anothermalloc()call, or (more modern) start zeroing it out for security and to speed upcalloc()). It doesn't change the pointer itself but it changes the data that was pointed to (or it can, anyway, which is why the pointer shouldn't be used after being freed). -

Stefan over 14 years@DrPizza: I've just found an argument why one should set it to

NULLto avoid masking errors. stackoverflow.com/questions/1025589/… It seems like in either case some errors get hidden. -

Secure over 14 yearsBe aware that a void pointer-to-pointer has its problems: c-faq.com/ptrs/genericpp.html

-

StevenWang over 14 years@ALL: And another question, so why wasnot the system designed to set the pointer null in the function

StevenWang over 14 years@ALL: And another question, so why wasnot the system designed to set the pointer null in the functionfree()...I thnk that will more convenient -

visual_learner over 14 years@Secure - Interesting. It seems that the best solution (IMHO) is the macro approach based on this FAQ.

-

visual_learner over 14 yearsAs I said,

free(void *ptr)cannot change the value of the pointer it is passed. It can change the contents of the pointer, the data stored at that address, but not the address itself, or the value of the pointer. That would requirefree(void **ptr)(which is apparently not allowed by the standard) or a macro (which is allowed and perfectly portable but people don't like macros). Also, C isn't about convenience, it's about giving programmers as much control as they want. If they don't want the added overhead of setting pointers toNULL, it shouldn't be forced on them. -

Secure over 14 years@Chris, no, the best approach is code structure. Don't throw random mallocs and frees all over your codebase, keep related things together. The "module" that allocates a resource (memory, file, ...) is responsible for freeing it and has to provide a function for doing so that keeps care for the pointers, too. For any specific resource, you then have exactly one place where it is allocated and one place where it is released, both close together.

-

visual_learner over 14 yearsThe macro shouldn't be in bare brackets, it should be in a

do { } while(0)block so thatif(x) myfree(x); else dostuff();doesn't break. -

visual_learner over 14 years@Secure - Well, yeah, the best solution is always writing your program correctly in the first place, but that can't always happen. That's why people practice defensive coding habits.

-

Secure over 14 years@Chris, actually I'm talking about DRY - Don't Repeat Yourself, one of the most defensive coding habits I've learned. It can always be done, maybe except for the quick one-time-run hack scripts that have to be finished yesterday, but there you won't care for the pointers, too... and except when you have to maintain a legacy codebase... However, DRY is strongly related with modularization and code reuse and will nearly always effectively save you time and nerves in the long run.

-

DrPizza over 14 years@Chris Lutz: Hogwash. If you write code that frees the same pointer twice, your program has a logical error in it. Masking that logical error by making it not crash doesn't mean that the program is correct: it's still doing something nonsensical. There is no scenario in which writing a double free is justified.

-

AnT stands with Russia over 14 years+1 This is actually a very good point. Not the reasoning about "double free" (which is completely bogus), but this. I'm not the fan of mechanical NULL-ing of pointers after

free, but this actually makes sense. -

AnT stands with Russia over 14 yearsThere are few things in the world that give away the lack of professionalism on part of the C code author. But they include "checking the pointer for NULL before calling

free" (along with such things as "casting the result of memory allocation functions" or "thoughtless using of type names withsizeof"). -

Left For Archive over 14 yearsDefinitely. I don't remember ever causing a double-free that would be fixed by setting the pointer to NULL after freeing, but I've caused plenty that would not.

-

Mike Clark over 13 yearsAs Lutz said, the macro body

do {X} while (0)is IMO the best way to make a macro body that "feels like and works like" a function. Most compilers optimize out the loop anyway. -

Dean Burge over 13 yearsI personally think that in any none-trivial codebase getting an error for dereferencing null is as vague as getting an error for dereferencing an address you don't own. I personally never bother.

Dean Burge over 13 yearsI personally think that in any none-trivial codebase getting an error for dereferencing null is as vague as getting an error for dereferencing an address you don't own. I personally never bother. -

Amit Naidu over 12 yearsWilhelm, the point is that with a null pointer dereference you get a determinate crash and the actual location of the problem. A bad access may or may not crash, and corrupt data or behavior in unexpected ways in unexpected places.

-

David Schwartz about 12 yearsIf you could access a pointer after freeing it through that same pointer, it's even more likely that you'd access a pointer after freeing the object it points to through some other pointer. So this doesn't help you at all -- you still have to use some other mechanism to ensure you don't access an object through one pointer after having freed it through another one. You might as well use that method to protect in the same pointer case too.

-

Eric over 11 yearsActually, initializing the pointer to NULL has at least one significant drawback: it can prevent the compiler from warning you about uninitialized variables. Unless the logic of your code actually explicitly handles that value for the pointer (i.e. if (nPtr==NULL) dosomething...) it's better to leave it as-is.

-

mozzbozz almost 10 years@DavidSchwartz: I disagree with your comment. When I had to write a stack for an university exercise some weeks ago, I had a problem, I investigated a few hours. I accessed some already free'd memory at some point (the free was some lines too early). And sometimes it lead to very strange behaviour. If I would have set the pointer to NULL after freeing it, there would have been a "simple" segfault and I would have saved a couple of hours of work. So +1 for this answer!

-

David Schwartz almost 10 years@katze_sonne Even a stopped clock is right twice a day. It's much more likely that setting pointers to NULL will hide bugs by preventing erroneous accesses to already freed objects from segfaulting in code that checks for NULL and then silently fails to check an object it should have checked. (Perhaps setting pointers to NULL after free in specific debug builds might be helpful, or setting them to a value other than NULL that is guaranteed to segfault might make sense. But that this silliness happened to help you once is not an argument in its favor.)

-

mozzbozz almost 10 years@DavidSchwartz Well, that sounds reasonable... Thanks for your comment, I will consider this in the future! :) +1

-

Coder almost 9 years@AnT "dubious" is a bit much. It all depends on the use case. If the value of the pointer is ever used in a true/false sense, it's not only a valid practice, it's a best practice.

-

David Schwartz over 7 years@Coder Completely wrong. If the value of the pointer is used in a true false sense to know whether or not it pointed to an object before the call to free, it's not only not best practice, it's wrong. For example:

foo* bar=getFoo(); /*more_code*/ free(bar); /*more_code*/ return bar != NULL;. Here, settingbartoNULLafter the call tofreewill cause the function to think it never had a bar and return the wrong value! -

jimhark over 5 yearsGood answer. I'd like to add one thing. Reviewing the bug database is good to do for a variety of reasons. But in the context of the original question, keep in mind it would be hard to know how many invalid pointer problems were prevented, or at least caught so early as to not have made it into the bug database. Bug history provides better evidence for adding coding rules.

-

jimhark over 5 yearsI don't think the primary benefit is to protect against a double free, rather it's to catch dangling pointers earlier and more reliably. For example when freeing a struct that holds resources, pointers to allocated memory, file handles, etc., as I free the contained memory pointers and close the contained files, I NULL respective members. Then if one of the resources is accessed via a dangling pointer by mistake, the program tends to fault right there, every time. Otherwise, without NULLing, the freed data might not be overwritten yet and the bug might not be easily reproducible.

-

mfloris about 5 yearsI agree that well structured code should not allow the case where a pointer is accessed after being freed or the case where it's freed two times. But in the real world my code will be modified and/or mantained by someone who probably doesn't know me and doesn't have the time and/or skills to do things properly (because the deadline is always yesterday). Therefore I tend to write bulletproof functions that don't crash the system even if misused.

-

Den-Jason over 4 yearsI always assign dead pointers to NULL since their addressed memory is no longer valid. I quite like the idea of using a replace value which is set to NULL in release mode, but something like

(void*)0xdeadbeefin debug mode so you could detect any errant usage. -

NeoH4x0r over 4 years@Paul Biggar: In my class (CPEN-3710 assembly programming at UTC), A pointer that is not explicitly initialized to a known value will be initialized to a random-garbage value. The point is that all variables should be initialized to a known value and provides both consistent and expected behavior.

![Learn How To Create A Secure Licensing System For Your Excel Software [FREE DOWNLOAD]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/l-tgyQvdC5g/hqdefault.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEcCOADEI4CSFXyq4qpAw4IARUAAIhCGAFwAcABBg==&rs=AOn4CLCX6D5mG-KppjRellWBoxObijvSuA)