Can I call a .cpp program in Bash?

Solution 1

You need to compile it first: first change the current working directory of Terminal to the path of your source file:

cd <path_to_cpp_file>/

Then compile the source file:

g++ myProg.cpp -o myProg

Then you can call the compiled executable from your bash script like this:

#!/bin/bash

# ...

<path_to_compiled_executable>/myProg

# ...

Solution 2

Since your real goal seems to be to automate whatever needs to be done to run your program, I suggest a different approach. Instead of writing a shell script, you can use a makefile. If you like, you can write a rule in your makefile for running your executable once it is built. You will then have two files--your C++ source code file and your makefile--and you will be able to run a single command that efficiently:

- Builds or rebuilds your C++ program, if and only if necessary.

- Runs your program.

The subsequent sections of this post explain why you can't call a .cpp file directly (but must create an executable from it first); how to install make, how to use it, and what it's doing behind the scenes; and how to avoid common pitfalls. But in case you want to get a feeling of what this approach looks like before delving in, you will run make run after putting this0 in Makefile:

all: myProg

run: all

./myProg

I like that better for this purpose than a shell script, and I think you might, too.

Background

Unlike some interpreted languages like Python and Bash, C++ is a compiled language.1 Programs written in C++ must be built before they are run. (Building is also sometimes called compiling, though compiling more properly refers to one of the steps of building.) You cannot run a C++ source code file; it must instead be compiled into object code2, in this case machine language. The object files must then be linked together, and even if there is only one, it must still be linked to any shared libraries it uses. Linking produces an executable which may be run.

In short, you have to build your program before you run it, the first time. Before subsequent runs it need not be rebuilt, unless you have changed its source code, in which case you must build it again if you want your changes to be reflected in the program that runs. The make utility is designed specifically for this sort of situation, where one wishes to perform actions conditionally depending on whether or not, and when, they have already been done.

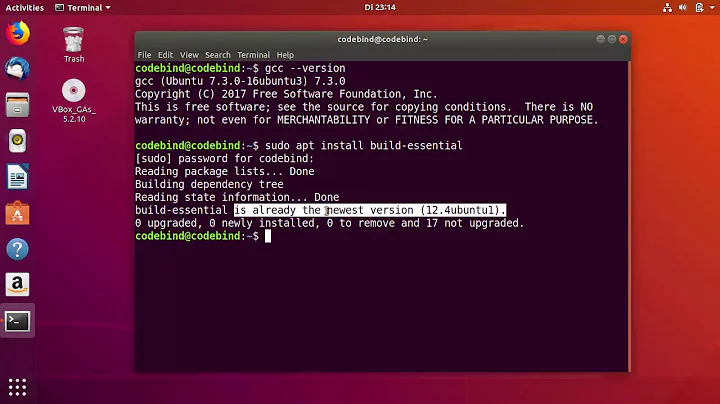

Getting make

You may already have the make command installed; try running it to find out. If it is installed, you'll see something like:

$ make

make: *** No targets specified and no makefile found. Stop.To get make you can install the make  package, but I suggest installing build-essential

package, but I suggest installing build-essential  which provides a number of other handy tools. (You might've installed build-essential

which provides a number of other handy tools. (You might've installed build-essential  to get

to get g++, which is one way you might already have make.) You can use the Software Center to install it or run the command:

sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install build-essential

make Without a Makefile

To see how make works, I suggest running it without a makefile first, passing it the basename of your source code file:

$ make myProg

g++ myProg.cpp -o myProg

$ ./myProg

Salam! WorldOn subsequent runs, make compares the modification timestamps (mtimes) on the input and output files, and won't rebuild your program unnecessarily:

$ make myProg

make: 'myProg' is up to date.When you change myProg.cpp, that updates its modification timestamp, so make will know to rebuild it. (You can also update a file's timestamp with the touch command, if you need or want to force any output files depending on it to be rebuilt. And of course, deleting the output files will also ensure they be rebuilt when you run make--just don't delete the wrong file!)

$ touch myProg.cpp

$ make myProg

g++ myProg.cpp -o myProgHow does make know what to do when you run make myProg?

- The

myProgargument tomakeis called a target. - Targets are often, but not always, the names of files to be created. Targets may be defined explicitly in a makefile.

- When a target is not defined in the makefile or (as in this case) there is no makefile,

makelooks for input (i.e., source code) files named in such a way as to suggest they are intended for building the target. -

makeinfers what utility and syntax to use in building a file from its suffix (in this case,.cpp).

All this can be customized, but in simple cases like this often doesn't need to be.

Creating a Makefile to Automate Building and Running Your Program

To automate more complex tasks than building a program from a single source code file, such as if there are multiple input files or (more applicably to your immediate needs) actions you wish done besides running the compiler, you can create a makefile to define targets for make and specify how they depend on other targets.

The first target defined in a makefile is the default target: it is what make attempts to build when run with no command-line arguments (i.e., when you run just make, and not something like make myProg).

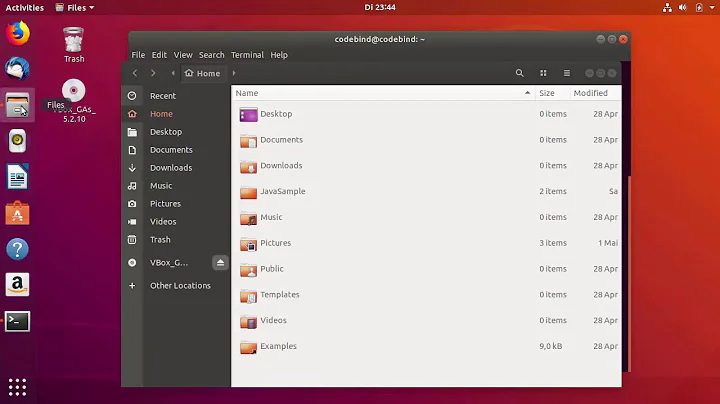

The usual way to use makefiles is to create a directory containing all source code files (and any other files) used to build your program, as well as the makefile, which is usually called Makefile. By that name, make will automatically find it.

To create a makefile you can use to run myProg and that will automatically build it first when necessary, put myProg.cpp in new, otherwise empty directory. Create another text file in that directory called Makefile.

You can use any text editor for this, but the recipe for a rule--the commands listed under it that will be run to make its target--must must be indented with tabs rather than spaces.3 So if your text editor is currently configured to indent with spaces when you press Tab, you should change this.

For example, in Gedit or Pluma, you would go into Edit > Preferences, click the Editor tab, and ensure Insert spaces instead of tabs is unchecked:

Many editors default to indenting with tabs and not spaces, so if you haven't changed this setting before, it may already be set correctly for makefiles.

Once you're in your editor and (if necessary) configured it to indent with tabs, put this in:

all: myProg

run: all

./myProg

If you copy and paste this, it will be wrong because spaces will be coped in even though your text editor doesn't make them when you press Tab. (This has to do with the way Ask Ubuntu displays code.) But you can simply remove the four spaces preceding ./myProg and press Tab to make a tab in their place.

Some text editors default to showing a tab as 8 spaces, or some other number. That's fine.

What That Makefile Does, and How to Use It

Use the command:

-

make, to build the program unless it is already built and the executable is current to the source code. Or, -

make run, to run the program, building it first if necessary (i.e., if there is no current executable).

This makefile defines two targets: all and run.

-

The

alltarget has no recipe of its own, but depends on themyProgtarget. This target is not explicitly defined, so it implicitly tellsmaketo attempt buildingmyProgfrom whatever source code files are available for it in the current directory. (See themakeWithout a Makefile section above for details.)Because

allis the first target explicitly defined inMakefile, it will be built whenmakeis run from the directory in whichMakefileresides. Thus we have set things up so runningmakeby itself is equivalent to runningmake all. -

The

runtarget runs the program. Its recipe consists of the command that does so,./myProg.rundeclares thealltarget as a dependency. This makes it so that when you runmake run,myProggets rebuilt if the currentmyProgexecutable is not current (or does not yet exist).We could just as well have made

rundepend onmyPrograther than onall, but we would still have needed the explicitalltarget (or an equivalent target of a different name) to preventrunfrom being the default target. Of course, if you want your program built and run even when you runmakeby itself, you could do this.Another benefit of depending on the

alltarget is in case later there are more actions that must be taken before your program ought to be run. You could then add a recipe to the rule forall.

Using the makefile to run the program looks like this, if it needs to be built:

$ cd myProg/

$ make run

g++ myProg.cpp -o myProg

./myProg

Salam! WorldOr this, if it doesn't need to be built:

$ make run

./myProg

Salam! WorldAnd if you just want to make sure the program is built (since the source code file was last modified) without running the program, simply run make with no arguments:

$ make # Here, I run make and myProg isn't current.

g++ myProg.cpp -o myProg

$ make # Running "make" again after "make" or "make run" does nothing.

make: Nothing to be done for 'all'.(make myProg will still work, too.)

A Refinement: Custom Compiler Flags

make is an extremely powerful tool, handy for simple purposes like this but also well suited to large, complex projects. Attempting to detail all the things you can do with make would be a whole book (specifically, this one).

But it occurred to me you might want to see warnings from the compiler, when something doesn't prevent the build from completing but still is a potential error. These won't catch all the bugs in the programs you write, but they may catch many.

When using GCC (as with the g++ command), I recommend passing at least -Wall to the compiler. This actually doesn't enable all warnings, but you can enable most of the rest with -Wextra. You may sometimes also want -pedantic. (See man gcc and 3.8 Options to Request or Suppress Warnings in the GCC reference manual.)

To invoke g++ manually with these flags, you'd run:

g++ -Wall -Wextra -pedantic -o myProg myProg.cpp

To make make invoke the C++ compiler (g++) with the -Wall, -Wextra, and -pedantic flags, add a CXXFLAGS= line with them to the top of Makefile.

CXXFLAGS=-Wall -Wextra -pedantic

all: myProg

run: all

./myProg

Even though myProg still exists and is newer than myProg.cpp, running make or make run after editing Makefile will still build the program again, because Makefile is now newer than myProg. This is a good thing, because:

- In this case, rebuilding the executable causes you to see warnings if there are any (there shouldn't be, for that particular program).

- More generally, sometimes when you edit a makefile it's because you want different files to be produced, or to be produced with different contents. (For example, if you had added the

-O3flag for heavy optimizations or-gto make the compiler generate debug symbols, the resultingmyProgexecutable would be different.)

Further Reading

- Exercise 2: Make Is Your Python Now in Learn C the Hard Way by Zed Shaw.

- The GNU Make Manual, especially 2.1 What a Rule Looks Like.

-

A Simple Makefile Tutorial by Bruce A. Maxwell, for information on other ways to use

make. - "Using Makefiles" (p. 15) and "Makefiles vs. Shell Scripts" (p. 62) in 21st Century C by Ben Klemens. Page numbers are for the first edition. (The second edition is probably better, but I only have the first edition.)

Notes

0: I recommend reading further to see how to make this work. But in case you want to attempt it first yourself: you must indent lines with tabs rather than spaces.

1: Strictly speaking, virtually any programming language could be either interpreted or compiled depending on what implementations for it have been written. For some languages, both interpreters and compilers exist. However, interpreted C++ is uncommon--though not unheard of.

2: Dividing building into compiling and linking, and calling the translation of a C++ source code file (.cc/.cpp/.cxx/.C) into object code compiling, is not the whole story. Programs in C and C++ (and some other languages) are first preprocessed. In your program, the C preprocessor replaces #include<iostream> with the contents of the <iostream> header file before actual compilation starts. And in the narrowest sense compiling converts source code into assembly language rather than object code. Many compilers (like GCC/g++) can combine compilation and assembly in a single step, and don't produce assembly code unless asked to do so.

While preprocessing is a separate step, GCC and other compilers automatically run the preprocessor. Similarly, they can automatically run the linker, which is why the entire sequence of preprocessing, compilation, assembly, and linkage is sometimes called "compiling" rather than "building." (Note also that building may contain more than those steps--for example, it may involve generating resource files, running a script to configure how things will be built, etc.)

3: You only have to indent with tabs in the makefile itself. Using a makefile doesn't impose any requirements on the way you write your C++ source code files themselves. Feel free to switch indentation back from tabs to spaces when you're working on other files. (And if you really don't like indenting with tabs in a makefile, you can set the .RECIPEPREFIX special variable.)

Related videos on Youtube

Admin

Updated on September 18, 2022Comments

-

Admin over 1 year

Admin over 1 yearI am new in Bash programming. I want to call my C++ program in Bash file.

My program is

myProg.cpp:#include<iostream> using namespace std; int main() { cout<<"Salam! World"<<endl; return 0; }And my bash file is

myBash.sh. How can I call my above .cpp program inmyBash.shfile? -

Thomas Ward about 9 yearsThis is not a good thing - this will compile the program each and every time. Unless you need that you should remove the

g++line. -

muru about 9 yearsPiledriver to crack a walnut. :P

muru about 9 yearsPiledriver to crack a walnut. :P -

gsamaras over 7 years

gsamaras over 7 years -

Cristian E. Nuno almost 5 yearsJust beginning to make the transition from Python to C++ so I really appreciate the thoroughness of this answer. Cheers!

Cristian E. Nuno almost 5 yearsJust beginning to make the transition from Python to C++ so I really appreciate the thoroughness of this answer. Cheers!